Numbers of Convicts (1788 - 1868)

More than 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1868.

About 80,000 convicts were sent to New South Wales (NSW), including a few to Port Phillip (future Melbourne) and Moreton Bay (future Brisbane) which were part of NSW until 1851.

Van Diemen s Land (Tasmania) received 69,000. The last convicts to land in eastern Australia were in Tasmania in 1852.

However, Western Australia (WA) only started receiving convicts in 1850 and continued to 1868. 9,700 convicts were sent to

WA to help its very small population to build public buildings. There were no female prisoners transported to Western Australia.

No convicts were sent to South Australia (SA).

Some 1040 ships carried convicts from England and Ireland and other places to Australia.

It is thought that about 165,000 departed from the ports of embarkation, and 3,000 died en route

(some of the numbers were taken from Southern Cross Genealogy).

The reasons for transportation to Australia

Life in 18th century England

In the eighteenth century (sometimes called the 1700s), the gap between rich and poor was huge. In England, King George III (cf. image on the left) lived in his palace on the rich side of London, while in the east of the city most people were poor and hungry. People began their working lives at the age of six, labouring long hours in factories for small wages.

Men had to live close to their workplaces, so hundreds of families would be crowded into just a few streets near butcher s shops and tanneries, where leather was made. The waste from these places, as well as sewerage from the houses, often ran openly in the street. Disease was very common in these slums. Nobody thought that life would get any better, so men and women tried to forget their troubles by getting drunk on cheap alcohol.

Crime

London s population doubled between 1750 and 1770. This rapidly rising birth-rate meant that suddenly England had a workforce made up of very young people who had no hope for the future. There weren t enough jobs to go round, and the only way people could survive was to steal.

More and more people were turning to crime, and there seemed to be no way to stop them.

Capital punishment

The government began sentencing criminals to death for almost any offence.

They hoped that capital punishment would frighten people enough to make them think twice before committing a crime. A murderer, a thief, or someone who cut down another person s shrubbery, could all get the same sentence.

Thousands of people were hanged for crimes that would only get them a fine today.

It was too expensive to build more jails, and the English upper class didn t want to have to see people suffering in chain gangs. Everyone wanted to get rid of the problem. The best idea seemed to be to take the prisoners to another country where England owned land, and leave them there. This was called transportation.

Transportation

Transportation had been used since the beginning of the eighteenth century to rid the English of their prisoners. Usually, convicts were taken to the British colony of America, but the American War of Independence (1775-1783) changed all that forever. The Americans no longer wanted to be a part of the British Empire, and were willing to fight for the right to govern themselves.

America won the war, and its new government told Britain not to send any more white convicts.

The Americans preferred to use black African slaves to do the work.

England had to do something soon about the overcrowded jails. A short-term solution was found.

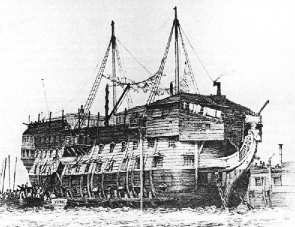

There were some old, disused ships known as hulks moored in the Thames River that flows

through London, and at sea-ports on the south coast of England. It was decided that these

would become floating jails. Convicts would eat and sleep on the hulks, and be taken to work

on the land every day.

While the hulks steadily filled with prisoners, the government tried to decide which of Britain s

colonies could support a penal settlement, which is an isolated community of convicts set up especially for the purpose of punishment.

The west coast of Africa was a possibility. So was Australia: the great southernland that no one

knew very much about. West Africa was the favourite option. Because it was closer to England it

would be cheaper to transport people there. The site was explored, but it was found to be unsuitable.

By 1785, living conditions on board the hulks were getting worse. Almost a thousand more convicts were being added to the floating jails each year. In 1786 there was a rebellion on one prison hulk - eight convicts were shot dead and 46 wounded. Lord Sydney, the Home Office Secretary, made the final decision. A penal colony would be established at Botany Bay.

The convicts lives and crimes

What kind of criminal came to Australia?

The First Fleet carried 736 criminals. They were all thieves. Over a hundred had used violence in carrying out their crimes (there were 31 muggers and 71 highway robbers on board), but none was transported for a violent crime, like murder. These first convicts were not naturally dangerous or violent. There was no Social Security in England at this time, and unemployment was even more of a problem than it is today. They were mostly hungry people who could not support themselves without stealing.

Painting of original first fleet leaving England in 1787 (Jonathan King)

The Original Fleet 1787-88

The original First Fleet of convicts left England just before first light on 13 May 1787,

in the seventeenth year of the reign of King George III. The fleet of eleven small wooden

sailing vessels weighed anchor off Portsmouth and sailed down the Solent Water heading

for New South Wales, discovered by Captain James Cook in 1770.

Criticised and condemned by the few who knew about them, 1,350 seamen, marines and

convicts set sail for an utterly unknown continent on the other side of the world, to found

a new nation in which no European had ever before lived. By midday all the ships had

passed the Needles and the afternoon saw them in the English Channel sailing before a

moderate southeasterly breeze.

They sailed to New South Wales via Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Cape Town, South Africa. The voyage took eight months and one week after which they anchored in Port Jackson, where they founded a settlement they called Sydney.

The First Fleet of 1787 was the greatest migratory voyage attempted by man. It travelled further than any other migratory passage, it carried more people, and it went to a land about which the voyagers ignorance was total. What is more, it was successful.

The ships were also very small with the smallest just a little over 21 metres. The flagship, HMS Sirius, was only half the size of an average merchant ship of the East India Company-and not one of them had been designed to transport convicts or stores on a voyage of this length-yet they all arrived at Botany Bay within three days of each other after eight months at sea.

Yet only 48 people died during the voyage, an amazing achievement in an age of malnutrition, appalling living conditions, medical ignorance, and low value on human life (the expression "may as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb" comes from these times when theft of livestock was a capital offence).

By contrast the Second Fleet-which sailed from England at the end of 1789-lost 267 people. The settlement that the First Fleet established at Port Jackson survived to spread and grow-ultimately into the modern Commonwealth of Australia.

Taken From: Webster s History of Australia. Published by Webster Publishing, 1997. Copyright Webster Publishing, and/or contributors.

Where did they come from and how old were they?

Most of the First Fleet convicts were citizens of London. On later fleets many Irish people were transported.

The average age of a convict was around twenty-seven years. The oldest male was Joseph Owen, who was in his early sixties; the youngest was a nine-year-old chimney sweep called John Hudson, transported for seven years for stealing some clothes and a pistol. The youngest female was Elizabeth Hayward, a clog-maker who stole a linen dress and a silk bonnet. She was thirteen. The oldest woman was Dorothy Handland, who hanged herself from a gum tree at Sydney Cove in 1789 at the age of eighty-four.

What did they look like?

Two hundred years ago, poor people were a lot shorter and scrawnier than the average person is today. This was because during the important growing years of childhood, their food had not been very nutritious or plentiful. Most of the male convicts were under 173 cm. Many of them were only about 160 cm, which nowadays is quite short even for a woman. The children that the convicts gave birth to later in Australia looked very different to their fathers and mothers. With a better diet and climate, they tended to grow up tall and broad, and were not as pale and hollow-cheeked as their parents.

What did they steal?

Most people stole food, or things they could sell easily.

John Price stole a goose; twenty-two year old Elizabeth Powley took some bacon, flour, raisins and butter from a kitchen; and West Indian Thomas Chaddick raided a kitchen garden for some cucumbers. Fifteen year old John Wisehammer stole some snuff (powdered tobacco that was sniffed, not smoked), and William Douglas picked a silver watch from a gentleman s pocket. All of these people were driven to petty crimes by hunger. All were transported to Australia.

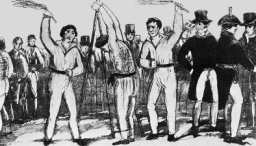

In general, the unluckiest convicts were considered to be those who were kept in government service. If you were a government man, you had the highest chance of ending up in the terrible chain gangs that slaved at the worst tasks, such as rock hewing and road building. Although conditions in many private posts were dreadful, at least the assignment system offered you a slim chance of a better life.

Flogging

Being sent to Australia was only the first punishment for the transportees.There were many more to greet them once they'd arrived.

The punishment most popular with officials was flogging, and the threat of the lash hung over the everyday lives of the convicts.

Copyright:

Most of the information on this page and most of the images were taken from the excellent "Australian CD-ROM School Project No. 2 &

Home Reference Library" by Maximedia Pty Ltd Australia:

http://www.maximedia.com.au - buyit@maximedia.com.au

Charles Bateson s "The Convict Ships 1787-1868" is regarded as the definitive guide to Australia s period of transportation. Information is given about the voyages to New South Wales, Norfolk Island, Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia. It ranges from the life on board for both crew and convict, right through to records of deaths, numbers of convicts and the length of each voyage. A comprehensive index of the convict voyages has been extracted from Bateson s text and is presented on our convict shipping pages.

Apart from describing each ship, the index gives the dates of each voyage, the ports they travelled between, the number of male and female convicts embarking and disembarking at each port and the route they took. Discrepancies between the number who embarked and disembarked were often due to deaths on board, transfers to other ships en route, or landing at other ports.

Transported convicts were handed over to the master of a ship at the beginning of the voyage and formally transfered into the custody of the Governor of the colony who was receiving them. Indents, or Indentures, were the documents used to record the transaction on arrival.

Conditions on Board

Convicts were housed below decks on the prison deck and often further confined behind bars. In many cases they were restrained in chains and were only allowed on deck for fresh air and exercise. Conditions were cramped and they slept on hammocks. Very little information seems to be available about the layout of the convict ships, but a few books do contain artists impressions and reproductions of images held in library collections.

Although the convicts of the first fleet arrived in relatively good condition, the same cannot be said for those that followed during the rest of the century. Cruel masters, harsh discipline and scurvy, dysentery and typhoid resulted in a huge loss of life.

After the English authorities began to review the system in 1801 the ships were despatched twice a year, at the end of May and the beginning of September, to avoid the dangerous winters of the southern hemisphere. Surgeons employed by the early contractors had to obey to the master of the ship and on later voyages were replaced by independent Surgeon Superintendents whose sole responsibility was for the well being of the convicts. As time went on, successful procedures were developed and the surgeons were supplied with explicit instructions as to how life on board was to be organised. By then the charterers were also paid a bonus to land the prisoners safe and sound at the end of the voyage.

By the time the exiles were being transported in the 1840s and onwards, a more enlightened routine was in place which even included the presence on board of a Religious Instructor to educate the convicts and attend to their spiritual needs. The shipboard routines on some of the Western Australian transports during the 1860s have been transcribed and are worth reading.

Ship Naming Patterns

One thing that confuses many researchers is the naming of the convict transports. A system adopted by Charles Bateson is in common use today and makes provision for the multiple voyages made by some ships, the use of different ships with the same name, and the changing description of some ships after they underwent a refit. The shipping lists on these pages describe when the ships were built and where, their size and their type.

Name-wise, the Roman Numeral after the ship s name describes the individual ship, while the number in brackets describes which voyage the ship was making. As an example, three different ships called Mary were sent to Australia with convicts and although the first two vessels only made one voyage each, the last one made five. In some cases, extra confusion arises when two ships with the same name were in active service at the same time.

Shipping Routes

Another point of confusion that often arises with convict voyages is the route they took. The convict shipping lists indicate if a ship travelled via other ports. That was especially so in the early days when ships were smaller, took longer and had to put in for supplies and repairs along the way. In later years, after other Australian settlements had been established, the transports often stopped at more than one destination to land convicts. From England the transports may have stopped off at Gibraltar, a port in the West Indies, South America, the Cape of Good Hope, and any one of the Australian penal settlements.

More than 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1868.

About 80,000 convicts were sent to New South Wales (NSW), including a few to Port Phillip (future Melbourne) and Moreton Bay (future Brisbane) which were part of NSW until 1851.

Van Diemen s Land (Tasmania) received 69,000. The last convicts to land in eastern Australia were in Tasmania in 1852.

However, Western Australia (WA) only started receiving convicts in 1850 and continued to 1868. 9,700 convicts were sent to

WA to help its very small population to build public buildings. There were no female prisoners transported to Western Australia.

No convicts were sent to South Australia (SA).

Some 1040 ships carried convicts from England and Ireland and other places to Australia.

It is thought that about 165,000 departed from the ports of embarkation, and 3,000 died en route

(some of the numbers were taken from Southern Cross Genealogy).

The reasons for transportation to Australia

Life in 18th century England

In the eighteenth century (sometimes called the 1700s), the gap between rich and poor was huge. In England, King George III (cf. image on the left) lived in his palace on the rich side of London, while in the east of the city most people were poor and hungry. People began their working lives at the age of six, labouring long hours in factories for small wages.

Men had to live close to their workplaces, so hundreds of families would be crowded into just a few streets near butcher s shops and tanneries, where leather was made. The waste from these places, as well as sewerage from the houses, often ran openly in the street. Disease was very common in these slums. Nobody thought that life would get any better, so men and women tried to forget their troubles by getting drunk on cheap alcohol.

Crime

London s population doubled between 1750 and 1770. This rapidly rising birth-rate meant that suddenly England had a workforce made up of very young people who had no hope for the future. There weren t enough jobs to go round, and the only way people could survive was to steal.

More and more people were turning to crime, and there seemed to be no way to stop them.

Capital punishment

The government began sentencing criminals to death for almost any offence.

They hoped that capital punishment would frighten people enough to make them think twice before committing a crime. A murderer, a thief, or someone who cut down another person s shrubbery, could all get the same sentence.

Thousands of people were hanged for crimes that would only get them a fine today.

It was too expensive to build more jails, and the English upper class didn t want to have to see people suffering in chain gangs. Everyone wanted to get rid of the problem. The best idea seemed to be to take the prisoners to another country where England owned land, and leave them there. This was called transportation.

Transportation

Transportation had been used since the beginning of the eighteenth century to rid the English of their prisoners. Usually, convicts were taken to the British colony of America, but the American War of Independence (1775-1783) changed all that forever. The Americans no longer wanted to be a part of the British Empire, and were willing to fight for the right to govern themselves.

America won the war, and its new government told Britain not to send any more white convicts.

The Americans preferred to use black African slaves to do the work.

England had to do something soon about the overcrowded jails. A short-term solution was found.

There were some old, disused ships known as hulks moored in the Thames River that flows

through London, and at sea-ports on the south coast of England. It was decided that these

would become floating jails. Convicts would eat and sleep on the hulks, and be taken to work

on the land every day.

While the hulks steadily filled with prisoners, the government tried to decide which of Britain s

colonies could support a penal settlement, which is an isolated community of convicts set up especially for the purpose of punishment.

The west coast of Africa was a possibility. So was Australia: the great southernland that no one

knew very much about. West Africa was the favourite option. Because it was closer to England it

would be cheaper to transport people there. The site was explored, but it was found to be unsuitable.

By 1785, living conditions on board the hulks were getting worse. Almost a thousand more convicts were being added to the floating jails each year. In 1786 there was a rebellion on one prison hulk - eight convicts were shot dead and 46 wounded. Lord Sydney, the Home Office Secretary, made the final decision. A penal colony would be established at Botany Bay.

The convicts lives and crimes

What kind of criminal came to Australia?

The First Fleet carried 736 criminals. They were all thieves. Over a hundred had used violence in carrying out their crimes (there were 31 muggers and 71 highway robbers on board), but none was transported for a violent crime, like murder. These first convicts were not naturally dangerous or violent. There was no Social Security in England at this time, and unemployment was even more of a problem than it is today. They were mostly hungry people who could not support themselves without stealing.

Painting of original first fleet leaving England in 1787 (Jonathan King)

The Original Fleet 1787-88

The original First Fleet of convicts left England just before first light on 13 May 1787,

in the seventeenth year of the reign of King George III. The fleet of eleven small wooden

sailing vessels weighed anchor off Portsmouth and sailed down the Solent Water heading

for New South Wales, discovered by Captain James Cook in 1770.

Criticised and condemned by the few who knew about them, 1,350 seamen, marines and

convicts set sail for an utterly unknown continent on the other side of the world, to found

a new nation in which no European had ever before lived. By midday all the ships had

passed the Needles and the afternoon saw them in the English Channel sailing before a

moderate southeasterly breeze.

They sailed to New South Wales via Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Cape Town, South Africa. The voyage took eight months and one week after which they anchored in Port Jackson, where they founded a settlement they called Sydney.

The First Fleet of 1787 was the greatest migratory voyage attempted by man. It travelled further than any other migratory passage, it carried more people, and it went to a land about which the voyagers ignorance was total. What is more, it was successful.

The ships were also very small with the smallest just a little over 21 metres. The flagship, HMS Sirius, was only half the size of an average merchant ship of the East India Company-and not one of them had been designed to transport convicts or stores on a voyage of this length-yet they all arrived at Botany Bay within three days of each other after eight months at sea.

Yet only 48 people died during the voyage, an amazing achievement in an age of malnutrition, appalling living conditions, medical ignorance, and low value on human life (the expression "may as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb" comes from these times when theft of livestock was a capital offence).

By contrast the Second Fleet-which sailed from England at the end of 1789-lost 267 people. The settlement that the First Fleet established at Port Jackson survived to spread and grow-ultimately into the modern Commonwealth of Australia.

Taken From: Webster s History of Australia. Published by Webster Publishing, 1997. Copyright Webster Publishing, and/or contributors.

Where did they come from and how old were they?

Most of the First Fleet convicts were citizens of London. On later fleets many Irish people were transported.

The average age of a convict was around twenty-seven years. The oldest male was Joseph Owen, who was in his early sixties; the youngest was a nine-year-old chimney sweep called John Hudson, transported for seven years for stealing some clothes and a pistol. The youngest female was Elizabeth Hayward, a clog-maker who stole a linen dress and a silk bonnet. She was thirteen. The oldest woman was Dorothy Handland, who hanged herself from a gum tree at Sydney Cove in 1789 at the age of eighty-four.

What did they look like?

Two hundred years ago, poor people were a lot shorter and scrawnier than the average person is today. This was because during the important growing years of childhood, their food had not been very nutritious or plentiful. Most of the male convicts were under 173 cm. Many of them were only about 160 cm, which nowadays is quite short even for a woman. The children that the convicts gave birth to later in Australia looked very different to their fathers and mothers. With a better diet and climate, they tended to grow up tall and broad, and were not as pale and hollow-cheeked as their parents.

What did they steal?

Most people stole food, or things they could sell easily.

John Price stole a goose; twenty-two year old Elizabeth Powley took some bacon, flour, raisins and butter from a kitchen; and West Indian Thomas Chaddick raided a kitchen garden for some cucumbers. Fifteen year old John Wisehammer stole some snuff (powdered tobacco that was sniffed, not smoked), and William Douglas picked a silver watch from a gentleman s pocket. All of these people were driven to petty crimes by hunger. All were transported to Australia.

In general, the unluckiest convicts were considered to be those who were kept in government service. If you were a government man, you had the highest chance of ending up in the terrible chain gangs that slaved at the worst tasks, such as rock hewing and road building. Although conditions in many private posts were dreadful, at least the assignment system offered you a slim chance of a better life.

Flogging

Being sent to Australia was only the first punishment for the transportees.There were many more to greet them once they'd arrived.

The punishment most popular with officials was flogging, and the threat of the lash hung over the everyday lives of the convicts.

Copyright:

Most of the information on this page and most of the images were taken from the excellent "Australian CD-ROM School Project No. 2 &

Home Reference Library" by Maximedia Pty Ltd Australia:

http://www.maximedia.com.au - buyit@maximedia.com.au

Charles Bateson s "The Convict Ships 1787-1868" is regarded as the definitive guide to Australia s period of transportation. Information is given about the voyages to New South Wales, Norfolk Island, Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia. It ranges from the life on board for both crew and convict, right through to records of deaths, numbers of convicts and the length of each voyage. A comprehensive index of the convict voyages has been extracted from Bateson s text and is presented on our convict shipping pages.

Apart from describing each ship, the index gives the dates of each voyage, the ports they travelled between, the number of male and female convicts embarking and disembarking at each port and the route they took. Discrepancies between the number who embarked and disembarked were often due to deaths on board, transfers to other ships en route, or landing at other ports.

Transported convicts were handed over to the master of a ship at the beginning of the voyage and formally transfered into the custody of the Governor of the colony who was receiving them. Indents, or Indentures, were the documents used to record the transaction on arrival.

Conditions on Board

Convicts were housed below decks on the prison deck and often further confined behind bars. In many cases they were restrained in chains and were only allowed on deck for fresh air and exercise. Conditions were cramped and they slept on hammocks. Very little information seems to be available about the layout of the convict ships, but a few books do contain artists impressions and reproductions of images held in library collections.

Although the convicts of the first fleet arrived in relatively good condition, the same cannot be said for those that followed during the rest of the century. Cruel masters, harsh discipline and scurvy, dysentery and typhoid resulted in a huge loss of life.

After the English authorities began to review the system in 1801 the ships were despatched twice a year, at the end of May and the beginning of September, to avoid the dangerous winters of the southern hemisphere. Surgeons employed by the early contractors had to obey to the master of the ship and on later voyages were replaced by independent Surgeon Superintendents whose sole responsibility was for the well being of the convicts. As time went on, successful procedures were developed and the surgeons were supplied with explicit instructions as to how life on board was to be organised. By then the charterers were also paid a bonus to land the prisoners safe and sound at the end of the voyage.

By the time the exiles were being transported in the 1840s and onwards, a more enlightened routine was in place which even included the presence on board of a Religious Instructor to educate the convicts and attend to their spiritual needs. The shipboard routines on some of the Western Australian transports during the 1860s have been transcribed and are worth reading.

Ship Naming Patterns

One thing that confuses many researchers is the naming of the convict transports. A system adopted by Charles Bateson is in common use today and makes provision for the multiple voyages made by some ships, the use of different ships with the same name, and the changing description of some ships after they underwent a refit. The shipping lists on these pages describe when the ships were built and where, their size and their type.

Name-wise, the Roman Numeral after the ship s name describes the individual ship, while the number in brackets describes which voyage the ship was making. As an example, three different ships called Mary were sent to Australia with convicts and although the first two vessels only made one voyage each, the last one made five. In some cases, extra confusion arises when two ships with the same name were in active service at the same time.

Shipping Routes

Another point of confusion that often arises with convict voyages is the route they took. The convict shipping lists indicate if a ship travelled via other ports. That was especially so in the early days when ships were smaller, took longer and had to put in for supplies and repairs along the way. In later years, after other Australian settlements had been established, the transports often stopped at more than one destination to land convicts. From England the transports may have stopped off at Gibraltar, a port in the West Indies, South America, the Cape of Good Hope, and any one of the Australian penal settlements.